Photo Credit: Front Row Studios-Australian Open Grand Slam Coaches Conference

Situation Training (ST) is a practical application of the international coaching trend called the Game-based approach (GBA). It allows players to learn the tactics and techniques required for successful play in real-life situations.

Too many players complain about losing to technically inferior opponents. The reason, few are taught to play the game. That is why so many players like doubles lessons. Coaches seem to ‘get it’ when teaching doubles. They prioritize strategy and positioning, decision-making and movement. If they would do the same for singles, they would have even more success. The strength of the GBA lies in the fact that tactics (what to do) are placed before technique (how to do). Tactics include critical elements required for successful gameplay, like decision-making, problem-solving, anticipation, etc.

My version of GBA is what I call “Situation Training” (ST). Learning tennis is more effective when it becomes about situations rather than strokes. In contrast to ‘stroke coaching,’ ST is about expanding the library of situations players can handle during play. Situation Training integrates tactical and technical learning.

In learning (whether business, medicine or tennis), the rule is: ‘The transfer of learning between any two situations is directly proportionate to the degree they are similar’. In other words, skills will transfer poorly from training or drills if practice does not re-create a realistic, game-play environment. This is the pitfall with many basket feeding drills. As a result, some proponents of GBA outright reject basket drilling. However, even basket-feeding drills can be an effective tool in the Situation Training System.

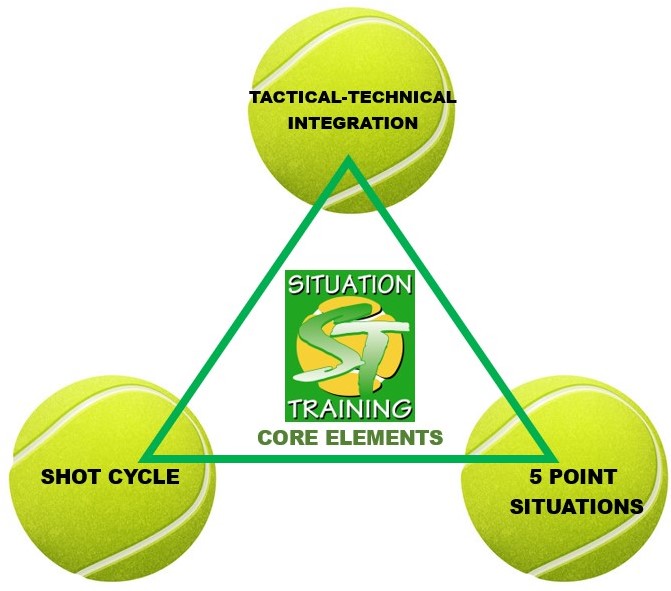

Three key elements are the core of the Situation Training system. Two are structural elements, and one is an essential concept.

ESSENTIAL CONCEPT: TACTICAL-TECHNICAL INTEGRATION

Situation Training adopts a Tactics-First approach. (for a more detailed article on Tactics-First, click here) It helps coaches evolve from being ‘stroke coaches’ to Situation Training. Using situations as building blocks brings together all the elements of tennis (tactics, decision-making, problem-solving, technique, psychology, etc).

For tennis, we can incorporate all these elements by placing them in a situational framework and emphasizing the proper relationship between tactics and technique.

In ST, technique is second (behind tactics) but never secondary. It is a critical component of tennis development. However, as mentioned previously, a traditional ‘Stroke-Model methodology’ with its emphasis on mimicking an idealized version of a stroke does not provide the flexibility and technical adaptation to use with ST.

ST becomes an alternative method for developing technique. It provides technical principles (not models) to use. This approach is called Tactical-Technical coaching.

THE 5 POINT SITUATIONS

The ST system starts with the ‘big picture’ tactical categories. These describe the general situations (relationship to opponent and court) players could be in during any point.

- Serving:

Every point in tennis begins with the serve (either 1st serve or 2nd serve).

- Returning:

Unless there is a double fault, every point includes a return of serve.

- Both Back:

This is where the players are located on or near the baseline.

- Approaching & at Net:

This situation includes the player moving forward and everything they can do at net.

- Passing:

This is the contrasting corollary to the ‘Approaching & at Net’ Situation where the player is trying to pass or lob.

Note: Every point obviously may not include all of the situations (e.g. a Serve & Volley pattern may skip the Both Back Situation). However, all of them need to be trained to develop a complete player. In every one of the 5 Game Situations, players can perform Neutral, Offensive or Defensive shots (except serving).

SHOT CYCLE

The next element of Situation Training is to define the situation more narrowly. For more specific training, coaches can use the “Shot Cycle” which describes the cycle of events that happen during an individual shot, from the player’s impact to the opponent’s and back again.

This framework gives coaches a critical tool to systematically organize training tactically.

The Shot Cycle includes two main ‘halves.’ A tactical situation that presents a problem & challenge to the player and a response that problem-solves the challenge. (For a detailed article on the Shot Cycle, click here.)

In Situation Training, the Shot Cycle needs to replace ‘strokes’ as the basic coaching building block

CONCLUSION

The core elements of Situation Training include Tactical-Technical Integration, The 5 Point Situations and The Shot Cycle. Acecoach.com provides multiple resources for each of these system elements.

Using ST, coaches can ensure their training and planning is directly connected to playing the game. More importantly, they will be more effective at helping students learn to play better tennis.

References:

1. Cayer, Louis. (1987). The Actions Method.

Presentation at the ITF Worldwide Coaches Conference. Mallorca, Spain.

2. Griffit, L.L., Oslin, J.L. & Mitchell, S.A. (1997). Teaching sport concepts and skills. A tactical games approach. Human Kinetics.

3. Jones, D. (1982). Teaching for understanding in tennis. Bulletin of Physical Education, 18 (1): 29-31.

4. Schmidt, R.A. & Bjork, R. (1992). New conceptualizations of practice: Common principles in three paradigms suggest new concepts for training. Psychological Science. 3, 207-217.

5. Thomas, K. T. and Thomas, J.R. (1994). Developing Expertise in Sport: The relation of knowledge and performance.

International Journal of Sport Psychology, 25, 295-312.

6. Vickers, J. N., Livigston, L.F., Umeris, S., Holden, D. (1999). Decision training: The effects of complex instruction, variable practise and reduced delayed feedback on the acquisition and transfer of a motor skill. 17, 357-367.

Leave a Reply