IT’S ABOUT TIME – Learning tennis as an open-skill sport

There is tons of information out there regarding how to play tennis. The bulk of it is technical in nature,

information about how to hit a ball. The

challenge is that success in tennis is every bit as much about when

to hit a shot as how to hit it. In other words, it’s about time (doing the right thing at the right

time).

The reason for this is that tennis is classified as an open-skill sport by motor learning researchers — a sport in which players must constantly adapt their movements to an ever-changing situation on the court. On every shot, a player must decide where to move, what shot to hit, and where to recover while awaiting the opponent’s next shot. The player’s movement and stroke execution must be continually adapted to the situation at hand.

Contrast this to a closed-skill

sport (such as diving, figure skating, gymnastics, etc.). Here the objective is

to execute pre-determined movements

in a precise and repeatable way, based on an idealized model or form. In closed-skill sports, performing the

movement correctly is how athletes gather points and win medals. Tennis

matches, by contrast, are not won by amassing points from judges who sit at

courtside, evaluating the form of each stroke.

The challenge is that success in tennis is every bit as much about when to hit a shot as how to hit it.

THE OPEN SKILL PROCESS

In the 1980’s, Canadian Coach Louis Cayer systemized a method of instruction based on the principles of open skill development. The approach was so effective that Tennis Canada adopted it as the official national coaching methodology. Cayer later went on to become Davis Cup Captain and National Head Coach. The principles have now also been adopted by the International Tennis Federation and numerous countries.

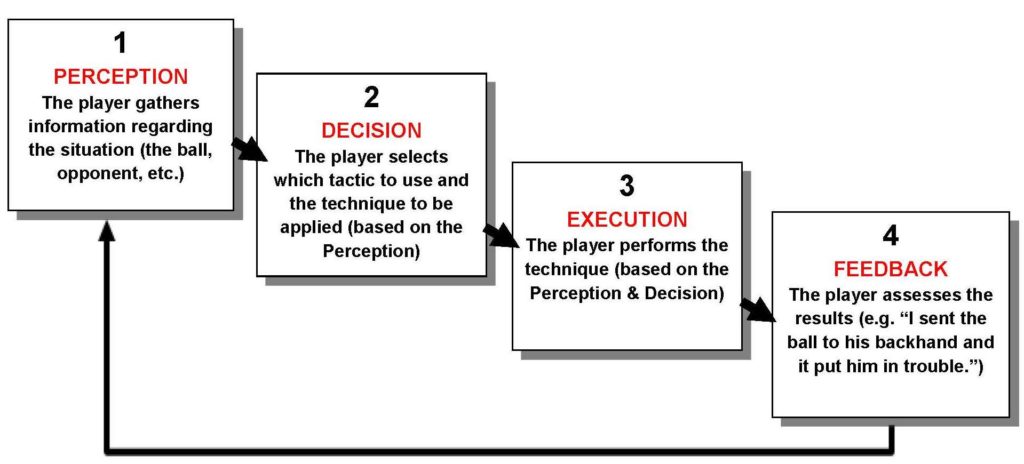

Cayer applied the research that revealed that, on every shot, a player goes through 4 steps of an information processing process (whether they are a starter player or a tournament pro). Closed skills in contrast. start with execution step:

A PROBLEM WITH TRADITIONAL TENNIS TEACHING?

For various reasons, tennis coaching evolved over the years into coaching tennis as a closed skill by making everything about performing specific technical movements in a prescribed form.

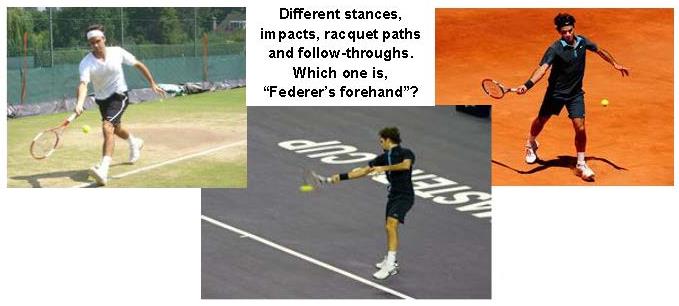

For example, when looking at the ‘forehand groundstroke’, a standard model will appear in the minds of most coaches and players. In recent years the content of the model has been changed to reflect the modern trends of the game (e.g. Semi-open stance, loop swing, Semi-western grip, etc). This ‘model thinking’ has even continued through the technological revolution (e.g. slow motion video of Federer’s “forehand”).

Traditional tennis coaching was based on the priority of conforming students to these models. The typical lesson consisted of a coach standing at mid-court delivering a soft feed to a student and harping about the elements of the, perfect ‘form’. Once the model stroke was reasonably stable, the coach sent the player back into the “real world”, expecting the player to successfully use the carefully-polished stroke in a live rally or match play situation. The typical result was the stroke quickly breaking down. Why? Because the player was not taught how to adapt it to real play situations. After the breakdown, the player would return to the coach only to have the cycle repeated.

A model based methodology impedes development of open skills because it falsely conveys there is a “one size fits all” technique that is good for every situation (e.g. “The basic forehand”). However, does the same technique occur if the forehand is performed from a wide ball or a 3/4 court low ball? Is it the same for an attacking shot, or a defensive one? Is it the same when receiving a high ball or sending a sharp angle? When the ‘basic stroke’ must be changed constantly to adapt to the situation it becomes the exception rather than the rule.

For example, in observations conducted on advanced beginners (2.0 Play Tennis Rating), the amount of time the ball was in range to perform the standard ‘model’ groundstrokes was maximum 30%. In other words, when novice players play (not drill), they are required to adapt in ways they have never been taught 70% of the time! Small wonder why many find tennis frustrating (especially after lessons).

True, many players eventually discover that stroke adaptation is critical to real world tennis. But how long does it take to achieve a reasonable degree of success? Months? Years? We now know there is a much better, and much faster way.

OPEN SKILL LEARNING

In any open-skill sport, technique is not an end in itself as in closed-skill sports. In an open skill, the situation rules. The player must correctly perceive the tactical situation to decide on which tactic gives the best chance for success. Technique becomes only a means to execute a tactic. The player must know what they are trying to do before learning how to do it. Technique should never be divorced from tactics, no matter what the level of play.

Since every skill must go through the open skill process, it is more effective to teach a player how to play (perform tactics) by applying ‘proper technique’ rather than teaching them ‘proper technique’ first (the strokes) and then tactics later. This ‘tactics later’ approach is not learner-centred because the ‘proper technique’ must always be adapted in ways not taught, applied to situations only mentioned, with decision-making skills never trained.

Playing is all about decision-making. In my experience, 40-60% of all errors can be traced back to some decision-making deficiency. The player didn’t nail down when to do the appropriate shot. For example, a player practices a bucket load of backhands. In the match during a rally, the ball comes a little faster (or deeper, higher, wider, etc.), the player doesn’t adapt the stroke and decide what to do on time resulting in an error. The majority of coaches and players watching would chalk it down to a technical error (e.g. they hit late) but that was only an outward symptom of not seeing what was going on and doing what they needed to do at the right time. Is the solution to practice another bucket of balls hitting early, or something more?

“MODELITIS” – A COACHING DISEASE?

Even with all the research and information about learning out there, the approach of giving players technical models to copy is so pervasive, I light-heartedly in our coaching education classify it as a disease for coaches called, “modelitis” . Do you suffer from a mild or severe case of modelitis? I have to admit that it is still so much a part of the coaching world I even get sucked into the mind-set occasionally.

The remedy is to remember that, since adaptation to a situation is the key distinction between open and closed skills, open skill learning must emphasizes technical learning in situations. By helping players to learn technique situationally, (includingperception and decision-making), players are empowered to perform their technique in more relevant and practical ways.

EVEN OPEN SKILL SPORTS NEED REPETITION TO LEARN

It is important at this point to note that, in an effective development process, a coach will frequently ‘close’ a skill to maximize specific technical repetition. This is very important to ensure technical fundamentals are developed. The trick is to not ‘model’ but build consistent, repeatable, motor patterns with a view to ‘open’ them up again and integrate them into point play.

CONCLUSION

Technical learning is not complete until players can improve how they read the situation and make good decisions about when to perform the technique and, just as importantly, when to not do it or adjust it. Open skill learning helps them to become smart and actually play tennis (not just stroke balls). Check out the many articles on acecoach.com to see tools and resources on how to coach this way.

Very useful and interesting article.

Furthermore, i think only the serve probably should have a Biomechanic model because it’s in the limit of closed skill and the movement of serve don’t need any adaptation or modification in this context.

What’s you point of view regarding that Mr Wayne.

Regards,

Hichem,

Thanks for the comment. Great that you are thinking about these things.

Serve is more ‘closed’ than say groundstroke rallies but, not fully closed. It has ‘closed’ reception (unless your toss is really bad) but open projection options. When you say ‘doesn’t need adaptation or modification’, I would point out that there needs to be adaptation for 1st Serve vs 2nd Serve, Ad side isn’t exactly the same as Deuce side, you must adapt to send it wide, at the body or down the center, technical changes have to occur to send it flat, with topspin or slice. In other words, 36 modifications that need to be made otherwise your serve will not be successful for the situation and tactical intentions.

I am not fond of biomechanical ‘models’ but, am fully on board with applying biomechanical principles to all of those 36 modifications to make them all effective and efficient.

Dear Wayne,

Thank your for your clear feedback.

Noted that.

Wish you all the best.

Regards,

Hichem

is there research out there that looks at the effectiveness of training open skills (like tennis) in a closed skill manner? Ie actually proves that open skills should be introduced in a closed way and this is the best approach for beginners?

Really good question Tom. There is no research I am aware of, as the two methods are a little bit like oil and water and don’t mix well. They come from two completely different starting premises. So, the research tends to focus on comparing starting and ending with the same approach. I have had coaches express that they feel compelled to start with closed skill training but usually, it s only because that is the only method they are familiar with and they can’t fathom how it even could be done in a different way. All I can say from experience doing it all closed, all open, starting closed and going open, and starting open and going closed is, consistently using an open skill methodology from beginning to end yeilds the most effective results.