INTRODUCTION:

It has been demonstrated that people take in information in 3 basic “Learning modes”; visual, verbal, and kinesthetic. The kinesthetic mode is about sensations and feelings of movement. Coaches typically are more comfortable and familiar with the verbal and visual modes.

Although the power of visual learning is well documented in motor learning, it really has maximum effect in the initial stages of learning technical skills. In my opinion, within a short time, the kinesthetic mode takes over as the primary mode. If a player cannot ‘feel’ correct technique, they cannot perform the skill on demand, modify it when required, or practice it on their own.

How can coaches tap in to the power of the kinesthetic mode to help players feel what they need to perform successfully? The key is to not teach, but rather, help players learn.

Within a short time, the kinesthetic mode takes over as the primary learning mode (when learning technique).

THE KINESTHETIC PROCESS IN TRAINING:

When a player performs their shot, they get “internal feedback”. In other words, they have a perception of how their feet, body, arm, and racquet are moving. The challenge is, their perceptions may be incorrect. For example, a player may think they are swinging low to high when in fact their racquet path is quite level.

Where a coach becomes valuable in the learning process is to provide “external feedback”. The coach becomes a mirror, letting the player know what really happened (e.g. “Your swing was level, drop your racquet more under the ball and come upward more exaggeratedly.”)

The goal of the coach in this process is to keep working with the player back and forth until what they feel (“internal feedback”) matches what the coach observes (“external feedback”). Once they really feel what they do, they are able to modify and self-correct if required. They will be self-sufficient (which should be the goal of every tennis player since coaching is typically not allowed during competition). This process is what I call, “bridging the gap”. Depending on the athletic ability of the player, they may have good, or poor, awareness of their movements.

An effective coaching technique to use to bridge the gap is called “Scaling”. The coach gives a range (e.g. “If 10 is the hardest you can thrust upward with your legs on the serve, and 1 is no thrust, what would you rate the serve you just did?”). Once the rating the player gives (from their internal feedback), matches the rating the coach gives (from the coach’s external feedback), the player’s learning will accelerate since they accurately feel what is actually occurring.

ADDRESSING THE MIND vs ADDRESSING THE BODY

In a typical session, coaches will often address the player’s mind. The false assumption is, if the player understands what to do and why, they will be able to perform correctly. It is common to hear coaches repeating the same instruction over and over again (e.g. “Prepare your racquet higher, prepare your racquet higher!”). Often, a tone of frustration can be heard in the coach’s voice as they can’t understand why the player, ‘doesn’t get it’ (especially after they explained and demonstrated it so well).

The truth is, the player’s mind absolutely understands however, their body doesn’t know what correct performance feels like so there is no way for the player to know if they are doing it well (e.g. they may feel like they are preparing very high when in fact they are not).

The coach may start by addressing the player’s mind, but must soon switch to addressing their body. “It doesn’t matter what you know, if you can’t feel it, you can’t fix it” is a quote that is applicable.

If you can’t feel it, you can’t fix it

To make correct performance of a technique become automatic, it takes plenty of repetition. All coaches agree, a player must, “hit a million balls” to become good. Every repetition grooves the technique (whether poor or good). But, even poor repetition can be a stepping stone to better performance if the player felt how they performed incorrectly, and the difference between the incorrect and correct performance.

Developing an ability to feel correct performance provides players with a reference they can use. It allows them to have a goal to work towards. They can feel what they did and, if it didn’t match the correct performance, modify it.

One way to connect the mind and the body is to use “analogies” to enhance understanding. These are common movement feelings that players may already be familiar with that can be tapped into. For example, many coaches use the analogy of throwing a ball to transfer to serving. Analogies build a ‘word picture’ that can connect all the Learning Modes (visual, verbal, and kinesthetic).

SHOT SENSATIONS (Feelings):

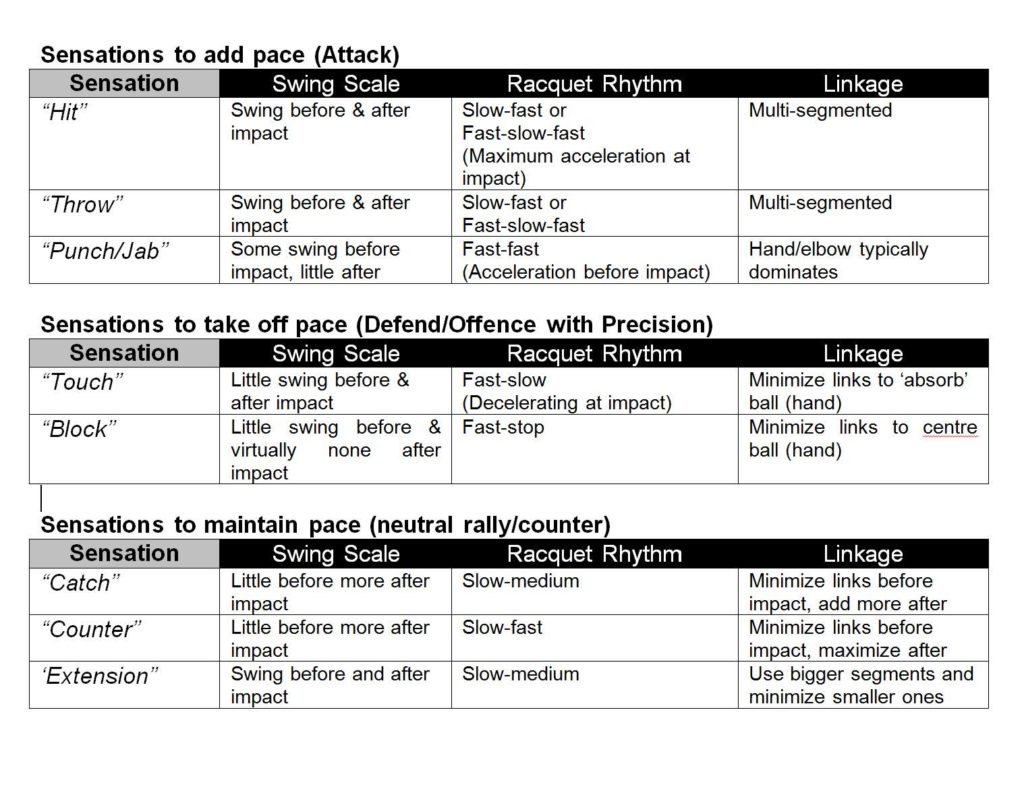

Each shot in tennis has a set of sensations that describe how the shot feels. Shot sensations are comprised of 3 main elements:

Swing Scale: Sensations include how much the racquet travels before, or after the impact. For example, a defensive shot may have little racquet work prior to, and after the impact. An attack shot may have more racquet preparation before, and a big finish after the impact. Typically a scale of 1 (minimal) to 10 (maximum) is used to describe the shot. For example, a full attacking groundstroke may be a 10/10 (10 backswing & 10 Follow-through) whereas a block volley may be a 1/0.

Racquet Rhythm: This is where the racquet moves slower or faster through the motion prior to, during, and after the impact point. For example, good serves often have a slow-fast rhythm. A ‘touch’ shot may have the racquet decelerate (fast-slow) to take pace off. Every shot has a rhythm that makes it more effective.

Linkage: Sensations also include which, and how many body segments are used in a shot (e.g. using shoulder, elbow, and wrist links to add pace on a forehand or, minimizing the links used for a block volley).

All these elements are combined to produce the ‘feel’ of a shot. These sensations can be grouped around specific key words. This is not an exhaustive list but covers the most common sensations players require for successful tennis:

- “Touch”: Used for taking pace off the ball and placing it precisely (e.g. drop-shot)

- “Block”: Used for handling high pace balls and re-directing the shot (e.g. blocking an overhead back with a lob)

- “Catch”: Used for maintaining pace and controlling the shot (e.g. warm-up volley)

- “Punch/Jab”: Used for adding speed to compact strokes (e.g. put-away volleys).

- “Hit”: Used for adding pace by increasing shoulder, elbow, or wrist linkage. A hit is when the racquet builds momentum then has a fast burst of speed in a short distances (e.g. attacking forehand)

- “Throw”: a throw is similar to a hit in that it builds momentum over a longer motion and uses multiple links. It may or may not have a speed burst through impact.

- “Extension”: Used to maintain pace through the shot. The finish is ‘let-go’ and there is typically an extended hitting zone (e.g. a deep baseline rally shot).

- “Counter”: Used for transferring the power of the ball received into the shot sent in order to ‘turn the tables’ and possible gain some advantage (e.g. returning a fast serve)

These sensations become very powerful learning tools in the hands of a smart coach. Getting players to ‘feel’ the way a shot is hit impacts them far more than trying to copy a sequence of movements.

Getting players to ‘feel’ the way a shot is hit impacts them far more than trying to copy a sequence of movements.

The shot sensations can also be organized in a table showing the connections to the feeling elements. These descriptions can help a coach better express the appropriate feeling to players.

CONCLUSION:

There is an ancient quote which applies to this topic, “What I hear, I forget, What I see I understand, what I do (feel) I know”. Helping players learn kinesthetically is a powerful tool to speed up the process of mastering tennis technique.

Check out the “Sensational Tennis” video series on Kinesthetic learning on the acecoach youtube channel

Leave a Reply