Any good development coach knows, whether for juniors or adults, tennis sessions should have a fun environment. It seems straightforward enough, but there is a bigger picture to comprehend? One of the advantages of perspective I have is directing a public tennis centre. We get players of all levels, ages and abilities, most coming for recreational tennis. On the other hand, we are also a designated Tennis Canada Tennis Development Centre, so we see the ‘performance’ side of things as well.

GETTING BETTER IS THE OBJECTIVE

The primary goal of tennis sessions is to learn and improve. Without improvement, players (and parents) will soon see the sessions are taking them nowhere. To improve, players need an environment with the critical elements of Goals, Repetition, and Feedback.

- Goals: The adage goes, “If you aim at nothing, you will usually hit it.” One can’t improve if they don’t know what they are shooting for. One trap development coaches can easily fall into is to give goal-less lessons and drills—activities without direction.

Performance coaches know how important goals are and also the measurement of those goals. The best performance coaches I know are ‘measurement freaks.’ They (and their players) are crystal clear on where they are at and where they need to get to.

- Repetition: One recent revelation in performance training is the concept of ‘Deliberate Practice’ (Click here to see the acecoach article). The 10-year/10,000 hour rule of required practice to master anything is well established. Players must get sufficient repetition to build the mental and motor patterns for high-level performance.

Development coaches would be wise to ask the question, “What are the players repeating most in my lessons? I know many stories of coaches who improved their lessons immensely after realizing what the players did most were things that didn’t improve tennis much (like standing in lines).

Without improvement players (and parents) will soon see the sessions are taking them nowhere.

We have a couple of helpful guidelines in our coaching education. One is counting the number of ball touches (We stole this one from performance soccer). Our top development coaches can do sessions where players contact the ball 500 times per hour (in a group of 6). The second guideline is repetitions per minute, per player. For motor pattern building to be effective, players need 8-12 repetitions per minute. With a group of 6-8 players, it may be on the low end of the range. It should be on the high end with fewer players on the court or very efficient activity set-ups. Both of these are excellent measures to see if your coaching is on track to improve players.

- Feedback: Improvement will happen faster if the quality of the repetition improves. Feedback is a ‘mirror’ the coach uses to help the player understand their performance. Players may not know if they are doing an action correctly or not. Without knowledge of ‘correct performance,’ the player can’t practise effectively on their own.

The coach helps by giving ‘external’ feedback (e.g. “Did you feel how that impact was too low, get the next one more at waist level.”) and/or setting up ‘internal’ feedback (e.g. player says ‘yes’ out loud if they impact the ball at an effective waist-level, out front, impact point). With an appropriate amount and type of feedback, the player will quickly get the feel of executing the action better. (click here for the first article in my coaching feedback series)

Tennis is a challenging game to play. The key to playing is getting over the ‘rally hump.’ Once a player can exchange the ball, the world of tennis opens up for them. Hitting a perfectly fed ball anywhere into the full court is not rallying. Holding a racquet up at the net and having the coach basically hit it with a feed is not volleying. It is possible for these activities to play a role in development, but things need to get to the goal of playing. The ITF defines it in the tag line for their Play & Stay initiative, paying tennis is to ‘Serve, Rally, and Score.

In other words, without improvement in the relevant technique required to play, my tennis life is limited.

WHAT ABOUT FUN?

Development coaches will often fall into what I call the ‘Entertainment trap.’ For sure, this is one I got caught in a lot as a young assistant coach. The logic goes like this:

“Players must have fun (my lessons are fun), when they have fun, they will come back. When they have fun they are happy, the parents are happy (and my Tennis Director is happy)”.

It all sounds good, but the logic breaks down when the equation’s improvement side is sacrificed on the altar of ‘fun.’ If they are having ‘fun,’ but after many lessons, they still can’t rally, their serve is a ‘pancake grip’ poke, and their volley technique looks like they are holding up a magnifying glass to the ball, they really aren’t learning tennis are they?

As an inexperienced coach, I would often play the wonderful games that circulate around the tennis world (especially with juniors). Every coach learns ‘tennis baseball’ and similar games. I asked a young coach one day, “Why do you play these games?” Of course, the answer was, “Because they are fun and (just to show me that my question was misdirected), the kids love them!”

My follow up response was to show a video of some excellent 10 and under kids playing great Orange ball tennis (see it here) and ask, “So how much tennis baseball would one have to play to get that good?” The perplexed look on their face told the story. No amount would make a kid get better.

The ‘Entertainment trap’ is to survive the lessons by keeping the kids ‘entertained.’ The challenge here is a losing battle. Tennis isn’t as ‘entertaining’ or ‘amusing’ as video games but can be just as (or more) ‘enjoyable.’

It all comes down to the coach’s definition of ‘fun.’ Our definition of ‘fun’ at my centre is to play tennis well. We know tennis is a great game (that’s why we play it, coach it, and even sometimes pay to get beaten up at tournaments!). The faster one can play tennis with some skill, the faster the fun mounts.

Our definition of ‘fun’ is to play tennis well.

The problem with those ineffective games is they try to disguise tennis as something else to make it palatable. The trap is that you have to conceal it constantly as the activities don’t open the door to having fun playing tennis. The kids also get hooked on the ‘sugar high’ of ‘amusement’ and don’t switch to enjoying the challenge of sport (with its accompanying work ethic and focus requirements).

We encourage our coaches to see themselves as nutritionists rather than clowns. Kids may ‘love’ cake, but if you gave them only what they wanted, they would soon suffer the consequences. However, if a nutritionist is good, they also have to motivate for good habits. Just putting a plate of bean sprouts in front of a kid and saying, “Eat it!” won’t change their diet either.

To be clear, nowhere am I advocating lessons shouldn’t be fun, just that the definition of fun must be in harmony with improving players and not sabotage that goal.

Improvement and Enjoyment

In the first level of Canadian Coaching Certification, candidates learn that the optimal environment for all tennis sessions must include both improvement AND enjoyment. Without the balance, the player’s experience can suffer.

Many coaches fall into the trap of making it an either/or choice. Either the session is ‘fun,’ or we work to get better.

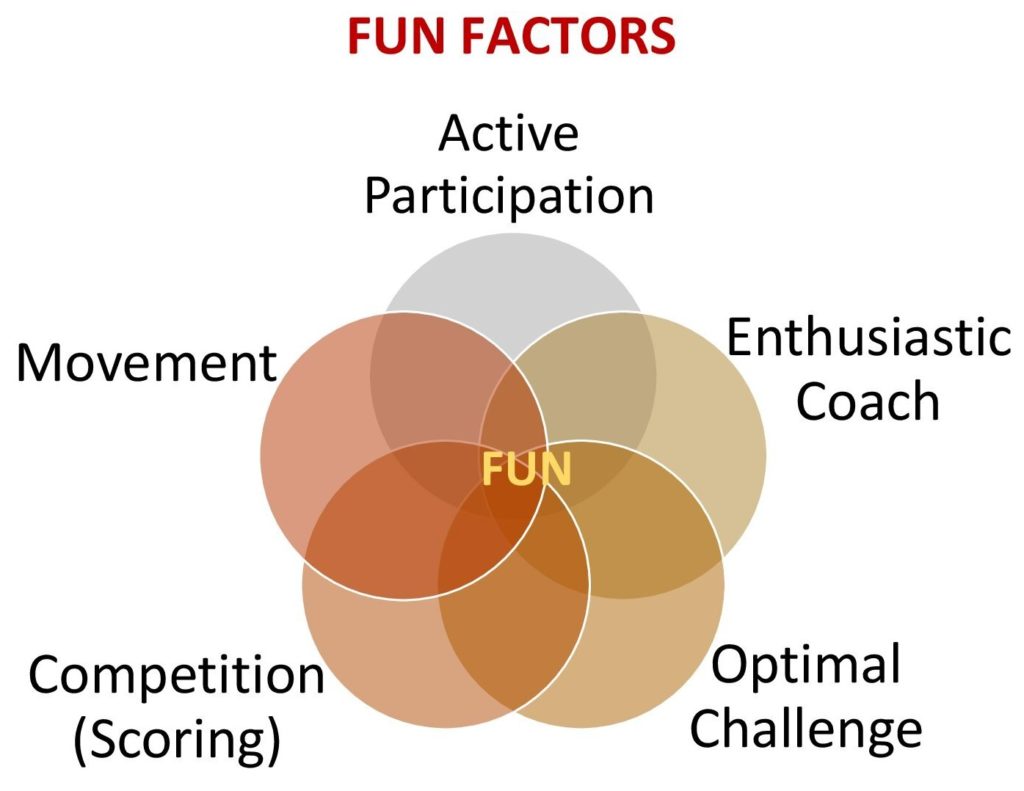

FUN FACTORS

Dry, rote repetition is not very inspiring for players (or coaches). The trick is to make every activity and drill fun (while getting in the repetition required). Often coaches feel stuck once they decide not to use the ‘entertainment’ activities. They can’t bridge the gap between activities that improve and those ineffective games.

The solution is to understand the principles that make those ineffective games ‘fun’ and apply them to effective practice activities. Coaches who learn and master what we call the “Fun Factors” have a powerful tool to drive learning.

Each Fun Factor is individually powerful, and activities become more fun as factors are added or less fun if factors are neglected. It is a specific environment that can be re-created by the coach whenever the need arises (which is every session).

The solution is to understand the principles that make those ineffective games ‘fun’ and apply them to effective practice activities.

Wayne elderton

These are the ‘Fun Factors’:

Active Participation:

Waiting in a line or sitting off doesn’t help enjoyment or improvement. The best activities start with the question, “How can everyone be involved?” Safety concerns may lead to not having everyone involved in the activity; however, they still should be given something to do, and any ‘wait time’ should be minimized.

Competition (Scoring):

The common denominator of every game (whether scrabble, football, or tennis) is that one can win. Adding scoring makes things more interesting. However, it shouldn’t be set-up for skilled players to dominate and less skilled players to be perceived as ‘losers’. Competition can be against self (e.g. “Anyone who beats their last score gets a point!”) or team on team (e.g. “Which pair can have the longest rally?”), etc.

This is challenging given the unequal levels typically found in most lesson groups. One easy solution is to work towards ‘sets’ of goals. For example, “Everyone can go for five. If you get five, you get a ‘super point!” In this way, the less skilled players can work towards their goal (getting one set) while the more skilled players can collect multiple sets (rather than getting to the number before anyone else and disengaging while waiting for the others).

Enthusiastic Coach:

International 10 and under expert Mike Barrell says it this way, “The drill is not the chocolate, the coach should be the chocolate.”

Fun is contagious and can be caught. If the coach is projecting the image of having a great time, some players may come along for the ride. We like to say that, “there are no boring activities, only boring coaches.” To be professional means to act to help the players (even if you don’t feel like it). This doesn’t mean every coach needs to be a party-going extrovert. Be yourself, but be fun.

Movement:

“Motion causes emotion.” Being dynamic is more fun than being static. The challenge is, some starter activities are too challenging if movement is also required. Even for advanced players, some skills don’t need much running around (e.g. serving practice).

The key is to understand the difference between ‘related’ and unrelated’ movement. For example, if you run out, hit your shot, and then recover back, I have put you through a ‘related’ movement (the movement that would happen if you were in an actual game).

If, however, you were doing an activity where you were bouncing the ball up to yourself (self-rally), the coach could make the skill challenging by not allowing your feet to move (making you work more racquet/ball control). However, the lack of movement may detract from the fun of the activity.

The coach could still include ‘unrelated’ movement. E.g. After you get three taps up, you have to run, touch a fence (line, etc.) and run back to your activity position. This would be an example of ‘unrelated’ movement that would make the activity more fun. You could even sneak in some ‘related-ness’ by having the footwork be tennis-specific (side shuffles, etc.)

Tennis shouldn’t be taught like golf. It is a dynamic game of movement. The more movement we can incorporate, the better for player development.

Optimal Challenge:

When players perform an activity that is too easy, they will lose interest quickly. If it is too difficult, they may engage a little longer but will disengage soon enough. An activity that has a success ratio of 50-70% will hold interest longer.

This is critical for development coaches to understand as they tend to put starter players in activities where they can be 100% successful. The trap (for kids especially) is the player will not try (which looks the same as being unskilled to a coach). The coach then makes the skill even easier (which loses the player completely). Many discipline problems occur because coaches don’t make activities challenging enough (so whacking the ball over the fence seems a better choice to the child).

Making activities optimally challenging can seem counter-intuitive to a coach since they need to set-up the activity so the player can’t be successful 30-50% of the time, but the result is worthwhile.

CONCLUSION

Coaches can optimize any training environment they create by understanding the balance between improvement and enjoyment. By understanding the improvement principles of goals, repetition and feedback, and the Fun Factors coaches have practical tools to create an environment that has effective practice and is enjoyable. This will lead to growth and retention. Who wouldn’t want to pay for a coach who can do that?

Leave a Reply