SEEING THE BIGGER PICTURE

Even though we are talking about technical observation, It is essential to note that technique does not exist in an isolated silo

There are four basic categories of skills in tennis. These make up what is commonly referred to as the ‘4 Performance Factors’:

- Psychological skills

- Physical skills

- Tactical skills

- Technical skills

When a player plays the game, they use all of these skills. Therefore, an effective coach must observe and evaluate skills in all four categories. Coaching through the filter of all 4 Performance Factors is called the ‘Integrated Approach.’ Click here for a more in-depth article on the Integrated Approach.

So, even though this article deals with technical observation, it is essential to be mindful of all 4 Performance Factors. The tactic, for example, is a critical consideration since technique is only a means to perform tactics (for an article on the tactical-technical connection, click here). In addition, the player’s physical capacity and psychological state also play an essential role in the process.

Performing shots in match-play is not a purely technical endeavour. Technical errors are often merely symptoms of other root causes. However, the trap in technical observation is that every error is technical. It occurs as a result of the physics of the shot; however, in actual matches, the source of many technical errors is often not technical. This creates a strange dichotomy where coaching through a purely technical lens doesn’t lead to what is required for successful tennis technique.

The source of many technical errors is often not technical.

Wayne Elderton – Coaching Educator

For example, a player may have the incorrect racquet speed on a volley (too slow, causing the ball to reflect off the strings and pop-up). Is the solution to drill the player’s volleys and tell them to move their racquet faster?

- Possibly, the root cause was poor decision-making (e.g., they got caught between deciding to put it away with power or hitting a drop-volley). Therefore, decision-making training would improve performing the volley.

- Possibly the root cause was psychological (e.g. they get tight on volleys that could end points or games). Therefore, mental training to deal with the anxiety of ‘finishing’ situations would improve performing the volley.

- Possibly the root cause was physical (e.g. they have poor stamina, so volleys that happen at the end of a prolonged match lack energy for sharp movements). Therefore, physical endurance training to maintain technique when tired would improve the performance of the volley.

Technique is learned to play the game, not to look good in drills. For the technique to be effective in match-play, the root causes need to be identified and addressed. If not, the performance in practice and drills may be perfect; however, technique useful for winning matches has not been learned. This is why coaches need to observe the technique in match-play whenever possible.

Technique should be observed in Match play situations whenever possible.

BARRIERS TO TECHNICAL OBSERVATION

Former Canadian Head National Coach and top international coach Louis Cayer has done coaching conferences and workshops worldwide. He typically found that only 20% of coaches (even experienced ones) accurately observed what happened during a shot (of course, we all think we would be in that 20%!)

An improper or flawed observation will lead to false conclusions. Observation is one of the most important skills a coach must master. Unfortunately, coaches rarely practice or improve their observation skills because they think observation ‘just comes naturally.’ Does every coach watching a skill performance see the same things?

So, observing a tennis shot may seem to be a simple task but, it has many layers and two main pitfalls to avoid. ‘Confirmation bias’ and focus issues.

Confirmation Bias

This is the first barrier to effective observation. ‘Confirmation Bias’ is a psychological term defined as:

‘The tendency to search for, interpret, favour, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one’s prior beliefs, pre-suppositions or values.’

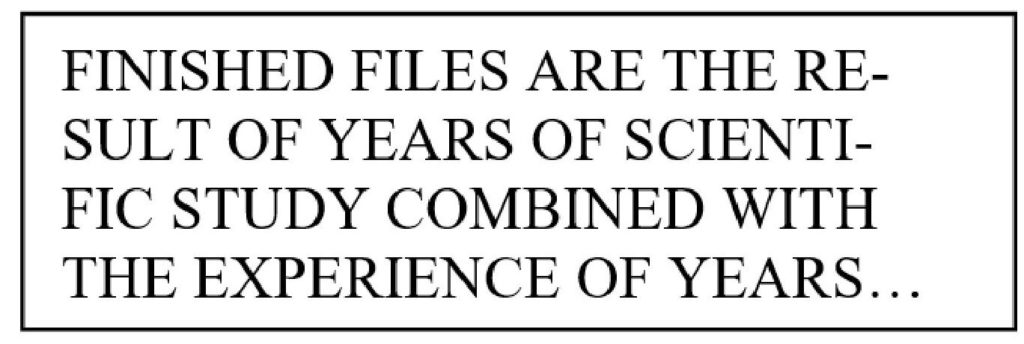

Here is a little test. Look at the sentence in the box below; give yourself a full minute to scan it well. Then, answer the question, how many letter “F’s” are in this sentence?

Did you scrutinize it thoroughly? Give it one more attempt. The answer is, there are six letter “F’s.” Is that how many you got? If not, look again.

Observation is not as simple as it seems. There are many brain processes, pre-conceptions, and even beliefs that can interfere with observing. In the case of the test above, the typical person doesn’t record the letter “F” when it’s in the word “of” because it registers the word as “ov” or an insignificant ‘filler’ word.

In addition, many coaches are entrenched in a technical way of thinking called “Model methodology.” In this approach, technical skills are grouped into stroke models. These are idealized versions of the forehand, backhand, serve, volley, etc. For example, the footwork model from decades ago for the groundstrokes said the ‘proper’ groundstroke had a linear weight transfer, always progressing from the back foot to the front foot (step & lean into the shot).

The problem? The majority of situations in today’s tennis include many types of steps: sideways, back, forward, on-the-spot rotations, etc. Athletic actions are required to play the game successfully, not robotic movements.

For observation purposes, these models are counter-productive. It is difficult to objectively observe when one has a very narrow definition of ‘correct.’ In reality, the situation determines what technique is the most successful or correct. A coach prejudices their observation by having these ‘one-size-fits-all’ models in mind. In other words, if you don’t believe a player should ever move backwards, when they do, it will not register in your mind (like the letter “f” in the word “of”). Or, you will immediately categorize it as ‘wrong’ and ignore it.

Focus Issues

People are wired for ‘selective attention. When directed appropriately, this becomes an asset and a disadvantage when the coach doesn’t select a specific focus for their observation. Take a look at this short video that illustrates the point.

I mentioned earlier that the best time to observe technique is during the reality of match-play. Any coach who has watched their players in matches knows how mind-numbing it can be (especially multiple players in multiple matches, which often occurs at tournaments).

Many things occur in every shot, so it is important to only look at one thing at a time. The trap most coaches fall into is, “Look at everything, and you will see nothing.” Research in observation shows that novice coaches see as many things as advanced coaches. The problem is, many of the things they record are not relevant to the performance of the skill. Advanced coaches zero in on the critical components of the performance. A systematic framework makes observation easier.

An effective coach takes into account these challenges when observing and seeks to be as objective as possible and identifies the focus of their observations.

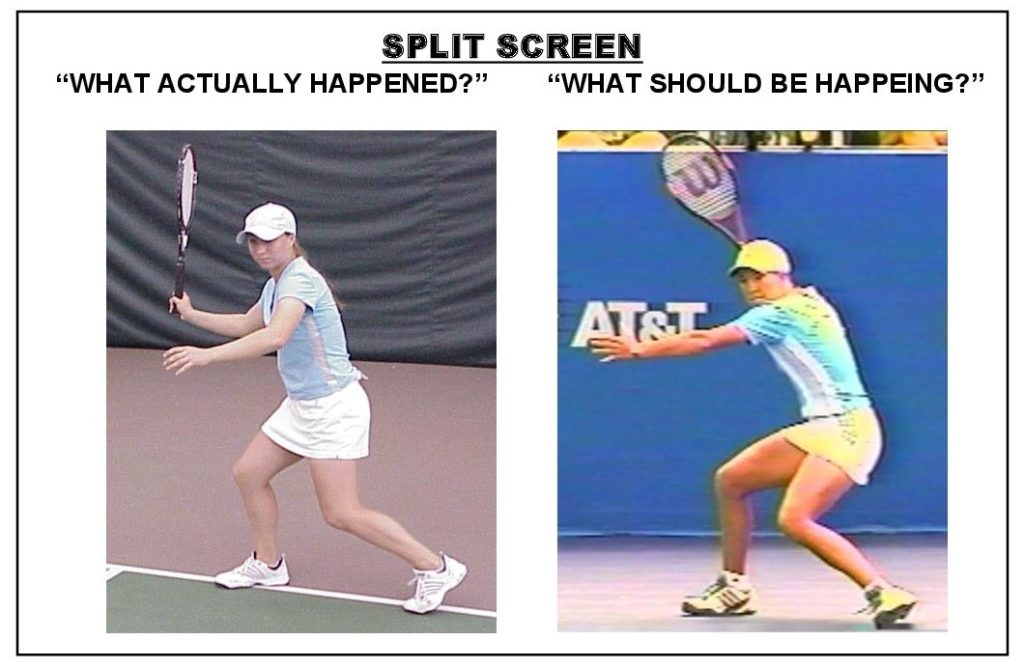

Keeping all this in mind, let us look at a beneficial observation system called ‘The Split-Screen’ which has two steps:

- The Observation Step

The goal of the observation step is to observe what occurs with no preconceived notions, beliefs, or judgments. Only then does a coach have the appropriate information to progress to the comparison step.

2. The Comparison Step

In the first observation step of the process, the coach asks: ‘What actually happened?’ Next comes the comparison step where they compare that observation to the answer to the question, ‘What should be happening?’ Combining these two elements creates a coach’s ‘Split Screen”.

I have found the quality of a coach’s Split Screen is an essential determining factor of their technical coaching level. Seeing the reality of what your player does, and comparing that to the observed reality of what an expert player does in the same situation, is critical for successful coaching.

TECHNICAL OBSERVATION FRAMEWORK

This observation system includes two key points captured in two basic questions that must be based on the intended tactic:

(NOTE: Not having the context of the intended tactic will trap the coach into ‘model-based’ technical thinking.)

- ‘Did the ball go where it was supposed to?’ (‘Control Observation’)

- ‘Did the ball have the appropriate power?’ (‘Power Observation’)

In the Control Observation, the shot is observed from the impact point downwards through the body to the ground. This leads the coach to the follow-up questions:

- ‘Did the shot have the appropriate timing?’

- ‘Did the shot have the appropriate P.A.S.?’ (Which elements were correct, which ones were not?) (Click here for an article on P.A.S )

- ‘Did the Bodywork allow for the correct P.A.S.?’ (The appropriate ‘Feeling’ for the shot) (Click here for an article on ‘Feelings’)

- ‘Did the Footwork allow for the appropriate Bodywork?’

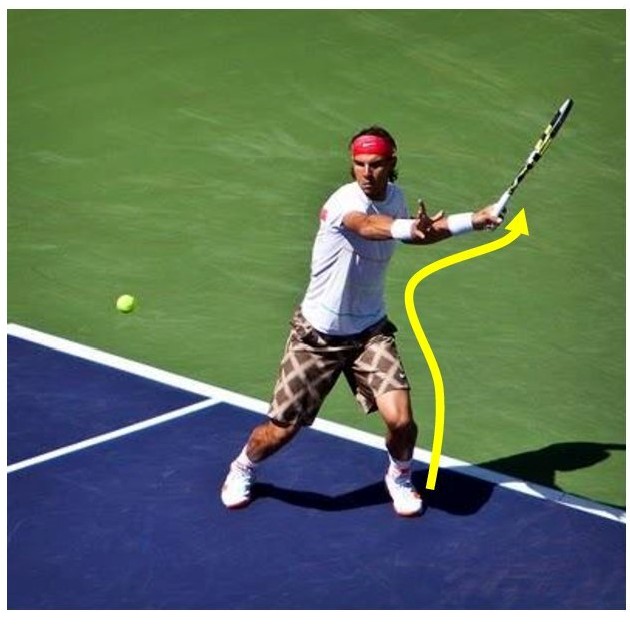

In the Power Observation, the shot is observed from the ground upwards to the impact point. This leads to the follow-up questions:

- ‘Was the ground force generated sufficient?’

- ‘Did the player transfer power efficiently through their body?’ (linkage of the segments maximizing or minimizing momentum as required)

- ‘Did the set-up allow for the appropriate footwork, body work & racquet work through the shot?’

It’s not just about fixing errors

It is important not to see this process as only ‘error detection.’ Having all the appropriate actions creates a positive ‘reference shot’ and gives a personal ‘Split Screen’ for both the player and the coach. For example, the coach could mention, ‘See how well that worked! Did you notice how your racquet sped up through the shot? Can you re-create that same shot?’ Understanding the correct performance of the shot empowers the player to self-correct by providing a tangible goal to achieve. Coaches need to become ‘success seekers’ rather than technical ‘fault-finders.’

Observation Practice

Online video clips of professionals in competitive situations can provide examples to study. Coaches can practice observing the clips at regular speed. You can then play the clips in slow motion or freeze the action to see if your observations were correct. Once your observation skills improve, you will be able to zero in on critical details more efficiently. Keep in mind that these video ‘stoke libraries’ are rarely categorized by situation. When doing this observation practice, make sure you identify the specific situation as much as possible to compare apples with apples.

CONCLUSION

By considering all the barriers to effective observation and applying a systematic technical observation system, a coach can objectively identify technical actions that will improve play. Whether identifying errors to correct or successful actions to repeat, the technique of the player is enhanced.

Leave a Reply