When we think of feedback, the most common picture is a coach providing input to a player. That is one type of feedback. However, there is an entire dimension of feedback that is not about the coach directly giving feedback.

REFRAMING TENNIS LEARNING AND SKILL ACQUISITION:

To understand the pros and cons of both types of feedback, we need to define some of the goals of learning and skill acquisition in tennis. If we frame a tennis match as a series of problems encountered by the player, then learning tennis is all about being a problem-solver. For example, receiving a difficult serve presents a reception problem to solve. If the opponent comes to the net, the problem to solve is how to pass them.

To find solutions, these are some of the abilities required:

- The ability to perform independently (since there is no coaching in tennis, during a match, the players must self-coach)

- The ability to adapt technique for the situation. Tennis is an open skill, so adaptation is a critical ability. (click here for video)

- The ability to apply effective decision-making.

- The ability to retrieve these solutions in the long-term (motor skill memory).

If we frame a tennis match as a series of problems encountered by the player, then learning tennis is all about being a problem-solver.

Wayne Elderton-Coaching Educator

EXPLICIT FEEDBACK:

When a coach directly provides feedback to the player, that is explicit feedback. In other words, it is a conscious conveying of information. For example, when a coach tells (or shows) a player to swing low-to-high for a topspin shot, that is explicit feedback. It is typically also directive (Click here for a link to an article on Directive versus Cooperative feedback) and prescriptive (corrective). (Click here for an article explaining prescriptive feedback)

As a young coach, I thought players couldn’t possibly learn it if I didn’t tell them the right stuff. Of course, if I had just applied some logic, I would have realized that not being privy to many lessons as a junior, I learned a lot through playing without a coach. So, ‘Unless you tell them they won’t learn’ is a false notion.

Based on the reframing paragraph above and all the ability requirements listed, explicitly giving players solutions to every problem has an inherent disadvantage. One doesn’t develop a problem-solver by constantly providing them all the solutions. Yet, this is the approach of the vast majority of coaches.

However, you eventually realize that people learn as much or more through the situations they experience than from the great nuggets of wisdom that flow from a coach’s mouth.

IMPLICIT FEEDBACK:

Implicit feedback is more complicated and sophisticated. It occurs when a player acquires knowledge (or skill) in an indirect and often unconscious process. Answers to problems are not provided directly; players find solutions for themselves.

In my experience, when a coach uses this approach, they can make real transformational change in a player. The reason is that, for the most part, people resist change (even if they are paying for it). When a coach takes them outside their comfort zone, this is often resisted even more. When I say ‘resisted,’ I am not saying they will refuse to listen. Most people will do whatever a coach tells them in a lesson, but they will often not believe it, trust it, or fully adopt and use it in a match. Their game isn’t transformed.

However, if they figure something out for themselves, the changes seem more ‘natural’ to them and are fully accepted (since they initiated the change).

I will apply one of my favourite quotes from an Australian Noble-winning author: ‘I don’t remember anything I was taught, only what I learned.’ All coaches need to reflect deeply on this quote.

The critical question is not, ‘What do I need to teach?‘ but rather, ‘What do they need to learn.’ That question takes a coach on a more effective and fulfilling journey (for both them and their player).

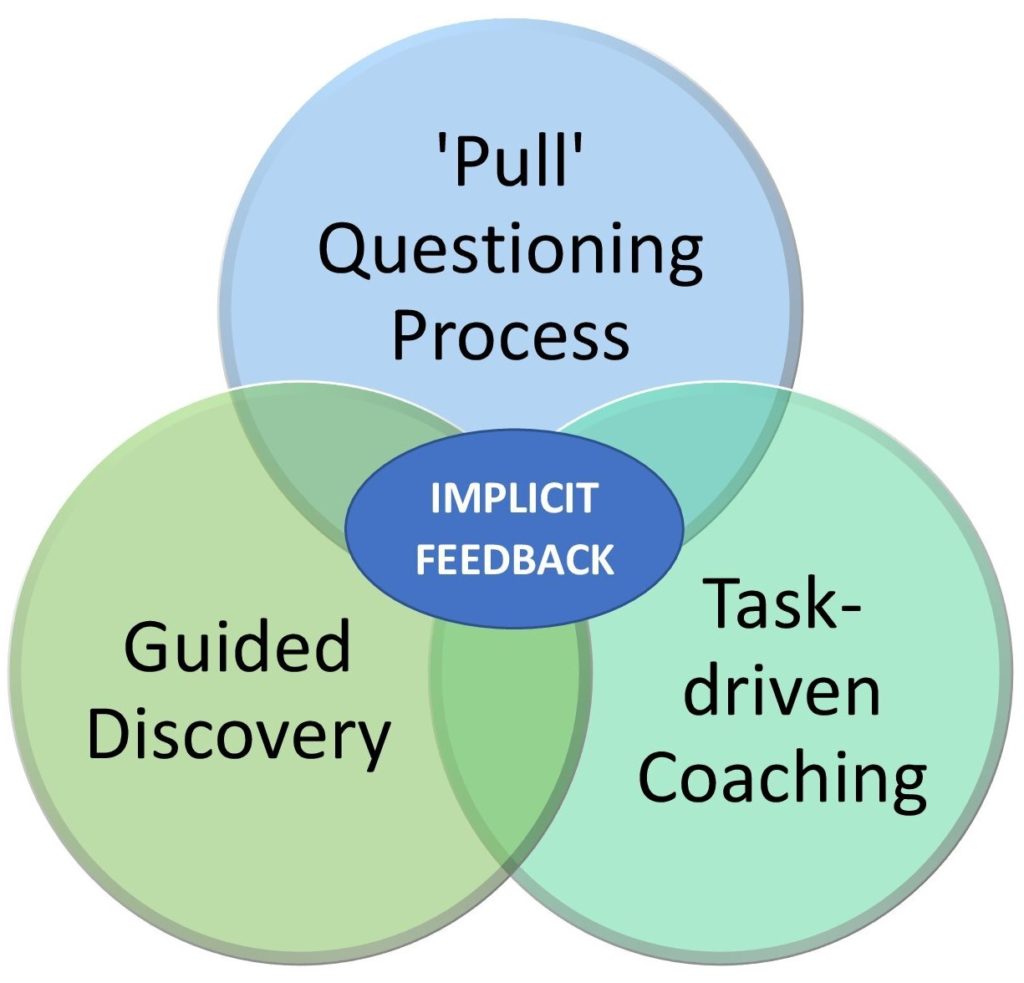

Two essential concepts factor into the explicit/implicit conversation:

- Guided Discovery

Utilizing implicit feedback does not mean leaving players to their own devices in endless wasted hours of trial and error. The coach becomes a ‘facilitator’ and steers players to solutions. This is called ‘guided discovery.’ The trick is to strike the best balance between explicit and implicit feedback without short-circuiting their learning process. In other words, they are empowered to find their solution, although it may never have happened in a timely way without the coach.

- Push vs Pull Learning

Another vital facet of the explicit/implicit discussion is the concept of ‘Push’ versus ‘Pull’ learning. Push learning is where the coach directly imparts the information (they ‘push’ it into the player). The player has no power to define the problem or find the action or knowledge required to find the solution or improve. It is all given to them. Push learning is explicit by nature.

‘Pull’ learning, on the other hand, is where the coach draws out of the player what is needed for performance. The drawing out can be done through questions and setting up an environment that allows players to find their own solutions.

This is not to say that there is never a time for ‘push’ learning; however, a balance is required to maximize effectiveness.

TWO WAYS TO PROVIDE IMPLICIT FEEDBACK

There are two avenues a coach can use to supply implicit feedback. They can be used independently or simultaneously. In both processes, the player is the centre of the process although the coach drives it:

- Utilizing a ‘Pull’ Questioning Process: In a cooperative approach, a coach poses questions and works with the answers provided. (click here for an additional article on Coaching Styles). By utilizing questions, the player is guided to frame the problems, explore possibilities and empower their improvement. In this process, the goal is for players to provide feedback to themselves. (Click here for an additional article on using questions in coaching). Questions can channel focus, invite creativity, and cement learning. The coach also gains critical insight into the player’s thoughts, knowledge, and attitudes through questions.

- Task-driven Coaching: This is part of a bigger process called the ‘Constraints-led Approach’. In this process, the environment itself provides the feedback. Rather than an intellectual process, it becomes a primarily experiential process. Rather than a ‘teacher,’ the coach becomes a master architect who designs tasks with parameters that pose problems to solve and challenges to overcome. These tasks will shape technique. When solutions are explored in a fun way, this process is often called ‘Playful Learning.’ To better understand how it works, I will provide an example.

CASE STUDY EXAMPLE – TASK-DRIVEN LEARNING

We decided to do a little experiment at the Academy. We noticed that, like most juniors, our players were very weak at using underspin groundstrokes (‘slicing’). Rather than explicitly teaching the slice (the way we usually do it), we followed another process. We would play a competitive game in every training session where the players could only slice (this would help with both the receiving and sending slice skills). The game would only last approximately 10 minutes. The coaches would still give technical feedback but ‘on the fly’ while players were competing.

Soon, we noticed that slice shots were being incorporated into the players’ match-play. By being exposed to slicing regularly, they were learning to slice short, deep, offensively, defensively, etc. This was an advantage over the explicit process, which had two main glitches. The first issue was that even though we spent time teaching them, we typically wouldn’t see it in their match-play much. Second, we would teach one specific slice situation, but they would still be in the dark about many others.

We were not teaching but creating an environment for them to learn the skill of slicing in neutral, offensive and defensive situations.

When we took the experiment further, we got the same result in our recreational groups (groups that many coaches would consider not good enough or not ‘ready’ to learn slice).

To be even more systematic, we modified the court during these various slice games to create different tasks. These tasks are problems players would have to solve with technical actions. For example, if they needed to learn to attack and to defend with precision and short angle slices, they could play on a court using only the service boxes out to the doubles sidelines (a wide/short court area). If they needed to learn sending and receiving deep, driving slices, we could play on ½ width of the singles court, but anything shorter than the service line was out. A wire could even be placed up across the net (air zone) for players to hit under to control the height for more ‘drive.’ We realized that we could create tasks to bring out whatever type of slicing they needed to learn.

This process resulted in two big wins:

- Improved adaptation skills: Players learned a greater range of different slice techniques and, much faster than when we taught them individually.

- Far more acceptance and integration of the skills: This was because rather than slice technique being imposed onto players by a coach trying to teach them, they were finding technical solutions on their own (with plenty of guidance from coaches). It was their technique. You always will be motivated to use what you come up with for yourself.

Through experience with this process, I have identified blocks of skills players need for successful tennis. In each of these categories, there are neutral, offensive and defensive variations:

- Slice Skills: Deep penetrating slices, low approaches, drops, angles, etc.

- Topspin Skills: Medium arcs, high loops, short power angles, etc.

- Overhead Skills: Power serves, defensive overheads, overhead power smashes, etc.

- Volley Skills: Touch, block, punch, catch, etc.

(Note: It is important to note that these are volley ‘skills’, not learning the volley ‘stroke’)

I have believed for a long time that technique should be learned through tasks. As a young coach, I often had the experience of players ‘pushing back’ and not using what I was teaching when they played. A coach is not a successful technical coach because of what they teach but because of how much they transform players’ technique when they play! A well-defined task is a more excellent teacher than I could ever hope to be. My job is to help their technique achieve the task (not teach them some technique because ‘Federer does it’).

A well-defined task is a more excellent teacher than I could ever hope to be

Wayne Elderton – Coaching educator

In reality, this is how all tennis techniques have been discovered. No coach in the history of the sport ever invented technique. Players needed to figure out how to perform the tasks necessary to win (e.g., hit harder, more accurately, more consistently, etc.). The result, technique that coaches then ‘reverse engineered’ and taught.

The challenge in creating an implicit environment is constructing tasks that require the appropriate technique to solve. Want a more powerful serve for U14 players? Make it so not only do they have to get the ball in, but it must hit the back fence before it bounces a second time. Want a deadlier drop shot? Make the task so the ball cannot clear the net too high but must bounce 3 times before the service line. Construct the task well and watch their technique transform (without the coach becoming the ‘dictator’). The only limitation is the coach’s creativity and understanding of tactics (The coach needs to know what the ball needs to do for the player to be successful at their level.)

Implicit learning by no means makes the coach irrelevant. They are still critical, so players don’t come up with inefficient technique (that waste energy, cause injury, etc.), The coach is needed to shortcut the time it takes players to find the solution.

CONCLUSION

Of course, a coach should use all the available feedback tools to be as effective as possible. There can often be interconnected feedback that flip-flops from implicit to explicit. A coach doesn’t have to make an either/or choice; however, using implicit feedback is less familiar to most coaches. Given that tennis is a problem-solving venture, harnessing the power of implicit feedback and guided discovery and ‘pulling’ more than ‘pushing’ is a goal all coaches need to strive for.

This is so good. I truly wish I would have worked on more of the “implicit” work with students years ago. I said “ I do not tell students what to do anymore I ask them questions. I was a guidance counselor for years and I found not giving advice but asking questions put us both on the same page. I have coached for years and I try to learn everyday. I see most coaches, teaching pros, not into learning everyday.