So how does one become good at tennis? This is a question on the mind of many tennis parents and players. Is it only the ‘talented’ players that achieve success?

Multiple research studies tracking people with high expertise in a field (sports, academics, music, the arts, etc.) have concluded that ‘talent’ is a myth. Every expert practitioner (in any discipline) put in plenty of training time. Of course, people come to any activity with various natural aptitudes; however, work ethic is the number one indicator of success, not natural gifts.

So, as the old adage goes, “practice makes perfect”… Or does it? Every tennis coach knows a player needs to “hit a million balls” to become proficient at tennis. Sport development experts point to the 10-year/10,000-hour rule to mastery. There are no short cuts to player development, but is it just a matter of putting in the time on court?

In the age-old debate of quantity vs quality, some new information has come to light. As crucial as volume is in tennis training, there are abundant examples of players worldwide mindlessly smacking balls for hours on end with no significant, measurable improvement in play. Tennis is horrible for players just hitting and calling it practice. Many parents and players get caught up in a ‘more is better’ mentality, which leads to injury and burnout.

In addition, many parents lament the challenge of juggling academics, other sports involvement, music, etc. Does every player who wants to be top-ranked in their region or country have to sacrifice a well-rounded life? If there was a way to become more efficient in training, a better life-tennis balance could be achieved.

The answer may be in a concept that has recently gained acknowledgement in the psychological and educational communities. It is called “Deliberate Practise.” As the name implies, the goal is to become more systematic and effective at using training time.

A psychologist at Florida State University, Anders Ericsson, who researches how superior performers become masterful at what they do, defines the concept this way:

“It’s activity that’s explicitly intended to improve performance, that reaches for objectives just beyond one’s level of competence, provides feedback on results and involves high levels of repetition.”

THE 5 CHARACTERISTICS OF DELIBERATE PRACTISE

In a recent lecture on motor learning at the University of British Columbia, Dr. Olav Krigolson summarized the key characteristics that differentiate deliberate practise (DP) from generic practise:

- Highly structured

- Specific and relevant

- Weaknesses are targeted, and performance monitored

- Mentally & physically focused

- Reward-less

These characteristics reveal essential distinctions between the activity most consider practise and the kind of practise that creates champions. Let’s take a closer look at each characteristic and it’s application to tennis. Each characteristic is listed separately; however, all the elements are interconnected.

- Highly Structured

DP is all about goal-setting and goal-achievement. It outlines a systematic process to master performance purposefully. Nothing is left to chance and done randomly. Not the schedule of practice, the duration, the time allotted to specific components, the measurement of skills, or the results to be accomplished. Players engaging in deliberate practise are clearly on a mission.

In tennis, the coach often plans practise with the player merely following the plan (with various degrees of commitment and motivation). This training must be supplemented by practice on their own. This is where determination and commitment are truly discovered. DP is planned, prepared, ordered and controlled.

2. Specific and Relevant

For tennis, DP is not a matter of practising serves, groundstrokes and volleys, but which serve and which groundstrokes, etc. For example, a player can hit a thousand forehands but, does that help their aggressive angled crosscourt forehand? They may practise serves, but how much repetition do they get on a topspin 2nd serve to the backhand on the ad side?

The specific shots practised must also relate to the situations players encounter when they play. In other words, practice must be relevant. For example, receiving an easy rally ball in practice and rallying it back (what many players do when they ‘hit’ together) is the opposite of what should be done in a match where the weak ball should be taken advantage of.

“Perfect practice makes perfect” is the correct saying (rather than “practice makes perfect”). Practising the wrong thing yields ineffectual skills.

Relevancy is also how the brain organizes any motor patterns it learns. A movement done for the sake of moving, or just because a coach says to do it that way, doesn’t build a strong motor pattern. If a player knows how the movement will help them and believes it is practical, they will learn it faster and completely ingrain it.

3. Weaknesses Targeted and Performance Monitored

Everyone likes to do what they feel competent at. It is uncomfortable to repeat something that exposes a lack of proficiency. That is why many players like point play rather than practise. They can more easily avoid their weaknesses.

Practising strengths is necessary to maintain them as strengths; however, smart opponents can exploit weaknesses. Most points are won by errors (not opponent’s great shots). DP objectively identifies what areas are not contributing to match performance and seeks to improve them.

Monitoring and measuring are critical to this process. If one goes to a personal trainer, the first thing done is to measure current strength, endurance, etc. Each session is designed to ‘raise the numbers.’ Tennis is guilty of consistently not measuring performance of tactical and technical skills. It typically only uses win/loss records and ‘outcome’ measurements (rankings, etc.) to show results. This is not helpful to a player trying to figure what components need training to improve results.

After serving a bucket of balls, do players know they are better at anything? In contrast, on the acecoach.com youtube channel, there is a series of videos called Performance On Demand criteria. This is an attempt to identify ways of measuring game skills to ‘raise the numbers.’

4. Mentally & Physically Focused

“Intensity” and “Intention” are hallmarks of DP. The physical effort required for the most difficult times in a match is replicated. Often, the intensity of training even exceeds the demands of the game.

For example, in groundstroke, footwork intensity shows itself in explosiveness used to get to the ball. However, in expert players, it is more noticeable in what is done in practice after they hit a shot. Is the recovery just as explosive and athletic or, does the player look like they are ‘finished’ after the hit? Although looking for perfection, the player must emotionally ‘let go’ of a poor shot and relentlessly re-focus on the task to come.

In regards to intention, tennis is rife with players hitting balls with no intention. Expert players know precisely what they want to do with the ball (Height, Direction, Distance, Spin, Speed). Not only that, but they practise controlling the ball even in difficult situations. They have a crystal clear intention for every shot. They are determined to master the ball and make it their slave no matter their position (e.g. defensively deep in a corner).

Tennis DP must include all the phases of play (neutral, defence, offence).

5. Reward-less

The tennis experience needs to be stimulating and ‘fun’ for starter players. However, once a player decides that they are no longer a ‘recreational’ player, the higher performance demands of competitive tennis require large amounts of skill repetition. Much of this repetition is not necessarily ‘fun’ (not entertaining). The only reward is the possibility of higher performance levels. Andre Agassi once said, “My goal is to improve 5% each year”. Strange talk for a millionaire.

It is not the status of winning, the financial possibilities, or the accolades that come from tennis success that drives the sacrifice required for DP. Improving is the reward in and of itself. Practitioners of DP learn to be driven by the pay-off of better performance.

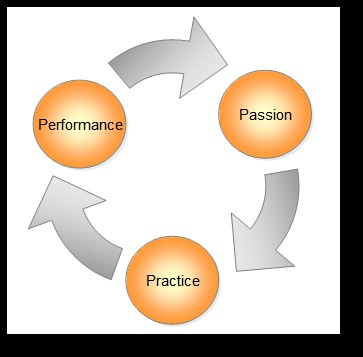

THE PASSION CONNECTION

In an article from the Wisconsin Technology Network, “Are top performers born or made?” the Passion-Practise-Performance chain concept for achieving world-class performance is emphasized.

“Deliberate practice drives expert performance. Passion provides the motivation necessary to practice rigorously. According to Professor Ericsson, top talents are able to practice long and hard and apply themselves more intensely than also-rans precisely because they are doing something that they love. If you don’t love what you do, then chances are good that you will never put in the time needed to master it.”

In other words, top performers don’t need the activity to be ‘fun’ to motivate them to do it. Their passion makes the activity worth-while to them, no matter how difficult, strenuous, and effortful it may be.

Once that passion is lost, the motivation to sacrifice goes with it. For example, world #1 player Justine Henin in her retirement speech, put it this way, “I always based everything on this motivation — this flame — that was in me. And once I lost that, I lost many, many things”. This statement (or something close to it) has been repeated in many professional retirement speeches.

OVERTRAINING

It is important to note that engaging in DP doesn’t mean players need to overtrain. “Staleness,” injuries and “burnout” are all consequences of not factoring recovery and regeneration into the practice schedule. There is a balance between the increased effort of DP and rest.

Studies show that to obtain optimal results, DP should be 1-2 hours per session (2 sessions per day is allowable) and limited to 3-5 days per week (Chase & Ericsson, 1982; Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977; Seibel, 1963). Anything more than 2 hours at a time obtains diminishing returns.

The tradition in tennis is that ‘serious’ players are on the court more. To ‘survive’ long-scheduled practises, players’ pace’ themselves and compromise the quality of the practice (plenty of ‘mindless’ hitting and purposeless point play.)

If a player is unable to recover from the stress of training, physical and mental fatigue will result, leading to the consequences listed above. More is not always better, and players need to ‘ease in’ to build up a tolerance for additional DP time.

CONCLUSION

There is no short cut to becoming an expert tennis player. The sooner those who desire to become performance players engage in regular DP, the sooner good players will emerge, the clock is ticking.

References:

- The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance, by Anders K Ericsson, Neil Charness, Paul J Feltovich, Robert R Hoffman, Cambridge University Press.

- Ericsson, K., & Krampe, R., & Tesch-Romer, C. (1993) “The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance” Psychological Review Volume 100: 363-406.

- Schmidt, R.A. & Bjork, R. (1992). New conceptualizations of practice: Common principles in three paradigms suggest new concepts for training. Psychological Science. 3, 207-217.

- Thomas, K. T. and Thomas, J.R. (1994). Developing Expertise in Sport: The relation of knowledge and performance. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 25, 295-312.

- Vickers, J. N., Livigston, L.F., Umeris, S., Holden, D. (1999). Decision training: The effects of complex instruction, variable practice and reduced delayed feedback on the acquisition and transfer of a motor skill. 17, 357-367.

Leave a Reply